In

The Nation, art critic Barry Schwabsky, an American living in England, writes:

In recent decades the philosophy of art has been much preoccupied with the enigma of why a given object does or doesn't count as a work of art. Since the challenge of Duchamp's Fountain and other readymades, according to the Belgian writer Thierry de Duve, the form of aesthetic judgment has undergone a shift: from "this is beautiful" to, simply, "this is art." For the philosopher, art status is like a light switch, either on or off. But the everyday art world is nothing like that, which is why the sociologist Howard Becker complains that the philosopher's art world "does not have much meat on its bones." For Becker, as for artists, collectors and critics, whether something is a work of art or not is the least of it. In the sociologist's art world, hierarchies, rankings and orders of distinction proliferate. Status and reputation are all, and questions about them abound. Why does the seemingly kitschy work of Jeff Koons hang in great museums around the world while the equally cheesy paintings of Thomas Kinkade would never be considered?...

The same kinds of question could be asked in other fields, but in the art of the past hundred years or so such questions have been of the essence: art is the field that exists in order for there to be contention about what art is. And such questions are not just for the cognoscenti; they've caught the fancy of a broad public as well. Once the man in the street saw a Picasso painting and said, "My kid could do better." Today, that child has grown up and is bemused but no longer outraged to read that a shark in a fish tank is worth a fortune but has been generously loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Now he admires, at least grudgingly, the clever scamp who could orchestrate that, and finds the whole affair rather interesting to talk about--even if the object itself might not, he suspects, be much to look at.

The idea that the man in the street talks about Damien Hirst or anyone else of his ilk is a very London-centric notion. On my walks, I drop in sometimes at the two local art galleries, which sell mostly to mid-level entertainment industry people concerned with impressing other entertainment industry people. Neither gallery would touch a stuffed shark. They sell mostly representational or quasi-representational paintings by living artists that are fairly attractive -- stuff that would be pleasant (or at least tolerable) to have in your house. There's more professional visual talent in LA -- directors of photography, set decorators, costume designers, editors, special effects directors, lighting men, etc. -- than probably anywhere else in the world. And the contemporary art scene is of little interest here.

This is not to say that at the high end of the LA social scale, the values of the contemporary art world are not upheld. For example, LA's community-leader-for-life, billionaire real estate developer Eli Broad, has used his vast wealth to scar the city with his hideous artistic taste:

This is the enormous sculpture that Broad paid to have implanted outside the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. From one angle, it looks like a chicken's skeleton made out of old airplane parts. I guess its prominent position is supposed to be an "ironic" reference to Los Angeles's historic role in the airplane industry. It's a whole bunch of twisted airplane parts scrambled together like the worst airplane crash in the history of the world. My father, a stress engineer at Lockheed, spent 40 years squinting at microscopic photographs of metal fatigue precisely to prevent beautiful airplanes from turning into abortions like this -- because in the real crashes he investigated, where he spent weeks picking parts out swamps and wheat fields to figure out why the plane went down, intertangled with the metal bits were scraps of human flesh.

Schwabsky goes on to allude to the fact that the question of what get's called "art" in our culture is less philosophical than sociological:

One unusual aspect of the art world--at least among the people who buy art rather than make it--goes unmentioned by Thornton, although a number of her interlocutors subtly allude to it: the fact that, at least in the United States and England, art's collectorship is heavily Jewish, and perhaps to a lesser extent, so is its "administration." Consider that in London, the unprecedented intensity of interest in contemporary art might never have happened were it not for the efforts of two men, both Jewish: the Iraqi-born collector Charles Saatchi and Nicholas Serota, the director of the Tate Gallery. One collector compares an evening sale at Christie's to "going to synagogue on the High Holidays. Everybody knows everybody else, but they only see each other three times a year, so they are chatting and catching up." A Turner Prize judge compares art to the Talmud: "an ongoing, open-ended dialogue that allows multiple points of view." Thornton observes the director of Art Basel, the world's most important contemporary art fair, making his round of the stands: he shmoozes his clients, the dealers, in French, Italian and German, and, Thornton observes, "I believe I even heard him say 'Shalom.'"The implicitly Jewish ethos surely feeds into the feeling that the art world is somehow set apart, part of the establishment perhaps but only "in a funny sense."

It's important to keep in mind that the Museum of Modern Art in NYC is a high WASP creation -- the founding committee met in John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s living room.

Still, it's not just Jewish buyers, but also Jewish critics, too, who determine "what is art" these days, as Tom Wolfe pointed out in his wonderful little book

The Painted Word a third of a century ago. Rather than write about three famous gentile painters of the 1940s-1960s, Pollock, Rauschenberg, and Johns, he wrotes about the three Jewish critics, Greenberg, Rosenberg, and Steinberg, respectively, who explained why we should care about them.

And for awhile, Americans did care about contemporary art.

Time and

Life used to run detailed coverage of the New York art scene when I was a kid. But now, the near-universal opinion in America is that contemporary art of the airplane crash sculpure variety is not just a joke, but an unfunny joke, so nobody pays any attention anymore. Now that

Dave Barry has retired, I almost never hear about the British Turner Prize anymore in American publications.

I suspect that one reason that the contemporary art scene in Britain is going stronger than in America is because Britain has fewer Jews, so contemporary art got a later start as a big whoop-tee-doo, so the public hasn't gotten quite as sick of it yet.

The basic problem is that Jews tend to be cognitively stronger with words than with images, so they are better at making up theories about why a stuffed shark is art rather than determining which art objects are beautiful and which are not. (To see how stark the ethnic cognitive divide is, look at lists of nominees for the Oscar in

Best Cinematography vs. the

Oscar nominees for Best Adapted and Best Original screenplays.)

When artistic status is largely determined by critics and collectors who, on average, come from a culture where people are cognitively stronger with words and numbers than with images, who are better at making up verbal theories than at painting pictures, you get in-joke art for people who want other people to notice that they are smart enough to get the joke.

My pet peeve, of course, is that

golf course architecture, which functions exactly like a traditional art form, is never considered "art." (The pictures are from the

Cypress Point Golf Club, designed in the 1920s by Alister MacKenzie.) Golf course architecture has had its ups and downs, but it hasn't driven itself into a ditch like contemporary art. For once, the WASP upper class, which runs the United States Golf Association, didn't lose it head. It kept sending the U.S. Open back to the great pre-1930 courses, keeping alive old standards of excellence.

Thus, here's the last course designed by Mike Strantz, the remake of the Monterey Peninsula Shore Course, before his death at age 50 in 2005 (golf course architecture has needed a romantic hero who died young):

Cognitive ability makes a big difference in art criticism. For instance, I have a decent two-dimensional visual capability (I can often figure out the designer of an unknown golf course I see from an airplane), but I'm weak at three dimensions. For a long time, this lack didn't stop me from confidently sounding off about golf course architecture. But as I've gotten to know the inner circle of golf architecture aficionados over the last few years, people like electrician Tommy Naccarato, one of the most influential amateur enthusiasts in the country, who has on file in his brain 3-d maps of thousands of golf holes, I've found myself with less to say on the subject as I better grasp my shortcomings. It's not just that they've worked harder at understanding golf course architecture than I have, but that they're smarter at it than I'll ever be.

My published articles are archived at iSteve.com -- Steve Sailer

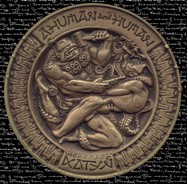

Szukalski’s politics weren’t helpful. In Chicago in 1914, to which his blacksmith father had brought him a half decade earlier, he was training 20 Polish boys in the manual of arms, “So when the time comes they will be ready to go back and fight for the freedom of Poland.” Polish nationalism, however, was not exactly the most career-promoting ideological obsession for a 20th-century artist. To the right is his

Szukalski’s politics weren’t helpful. In Chicago in 1914, to which his blacksmith father had brought him a half decade earlier, he was training 20 Polish boys in the manual of arms, “So when the time comes they will be ready to go back and fight for the freedom of Poland.” Polish nationalism, however, was not exactly the most career-promoting ideological obsession for a 20th-century artist. To the right is his  Warhol, in contrast, invented a more consumer-friendly role for the artist in a culture tiring of greatness. Andy pointed out, “Art is what you can get away with.”

Warhol, in contrast, invented a more consumer-friendly role for the artist in a culture tiring of greatness. Andy pointed out, “Art is what you can get away with.”